Page 14 - Layout 1

P. 14

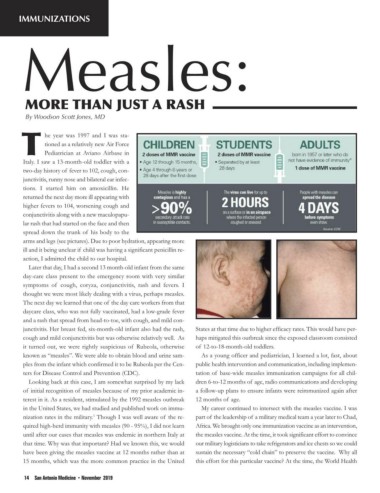

IMMUNIZATIONS

By Woodson Scott Jones, MD

he year was 1997 and I was sta-

tioned as a relatively new Air Force

Pediatrician at Aviano Airbase in

Italy. I saw a 13-month-old toddler with a

two-day history of fever to 102, cough, con-

junctivitis, runny nose and bilateral ear infec-

tions. I started him on amoxicillin. He

returned the next day more ill appearing with

higher fevers to 104, worsening cough and

conjunctivitis along with a new maculopapu-

lar rash that had started on the face and then

spread down the trunk of his body to the

arms and legs (see pictures). Due to poor hydration, appearing more

ill and it being unclear if child was having a significant penicillin re-

action, I admitted the child to our hospital.

Later that day, I had a second 13 month-old infant from the same

day-care class present to the emergency room with very similar

symptoms of cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, rash and fevers. I

thought we were most likely dealing with a virus, perhaps measles.

The next day we learned that one of the day care workers from that

daycare class, who was not fully vaccinated, had a low-grade fever

and a rash that spread from head-to-toe, with cough, and mild con-

junctivitis. Her breast fed, six-month-old infant also had the rash, States at that time due to higher efficacy rates. This would have per-

cough and mild conjunctivitis but was otherwise relatively well. As haps mitigated this outbreak since the exposed classroom consisted

it turned out, we were rightly suspicious of Rubeola, otherwise of 12-to-18-month-old toddlers.

known as “measles”. We were able to obtain blood and urine sam- As a young officer and pediatrician, I learned a lot, fast, about

ples from the infant which confirmed it to be Rubeola per the Cen- public health intervention and communication, including implemen-

ters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). tation of base-wide measles immunization campaigns for all chil-

Looking back at this case, I am somewhat surprised by my lack dren 6-to-12 months of age, radio communications and developing

of initial recognition of measles because of my prior academic in- a follow-up plans to ensure infants were reimmunized again after

terest in it. As a resident, stimulated by the 1992 measles outbreak 12 months of age.

in the United States, we had studied and published work on immu- My career continued to intersect with the measles vaccine. I was

nization rates in the military. Though I was well aware of the re- part of the leadership of a military medical team a year later to Chad,

1

quired high-herd immunity with measles (90 - 95%), I did not learn Africa. We brought only one immunization vaccine as an intervention,

until after our cases that measles was endemic in northern Italy at the measles vaccine. At the time, it took significant effort to convince

that time. Why was that important? Had we known this, we would our military logisticians to take refrigerators and ice chests so we could

have been giving the measles vaccine at 12 months rather than at sustain the necessary “cold chain” to preserve the vaccine. Why all

15 months, which was the more common practice in the United this effort for this particular vaccine? At the time, the World Health

14 San Antonio Medicine • November 2019